There's perhaps no name more auspicious in the wind band world than that of Percy Grainger, whose monumental work Lincolnshire Posy represents to many the pinnacle of craftsmanship for wind ensemble.

Renowned composer, pianist, and musical visionary, Grainger almost single-handedly elevated the wind band’s role from one of utility to one of artistry — with the help of a brief career as a U.S. Army Soldier and a life-long friendship with the West Point Band.

Born in 1882 in Melbourne, Australia, Percy Grainger’s natural talent at the piano took him around the globe from a young age, performing in his native Australia and across Europe, before making his way to the country he would one day call home — the United States of America.

After three years of acclaimed concert touring around the states, Grainger sought the make his stay in the U.S. permanent and enlisted as a Soldier in the Army Bands program in 1917.

Grainger enjoyed a brief but storied career in the Army. Though already an established pianist, he somehow managed to finagle a position as a saxophone player, despite any indication that he could play the instrument at all. In a similarly bizarre vein, he later served as oboe instructor at the Army School of Music — though one wonders how effective he was in that role when he himself confessed in a letter, “I long for the time when I can blow my oboe well enough to play in the band.”

For the bulk of his time in the Army, however, Grainger was able to focus on his true talents — playing piano, arranging, and, most famously, composing his own original works for American wind band. As Grainger began his Army service, the wind ensemble was just beginning its move from the realm of strictly utilitarian usage — marching, signaling, and ceremonial purposes — into a new era of embracing and incorporating elements of pure artistic merit as well, a move that Grainger’s unique, expressive, and avant-garde compositions would rapidly energize.

It was also during his military career that Grainger made the acquaintance of a fellow pianist named Francis Resta. Like Grainger, Resta would go on to be considered one of the visionaries of the wind band repertory, a role which eventually brought him to West Point as Teacher of Music and director of the West Point Band. Resta (who retired as an Army colonel) and Grainger’s relationship blossomed on stage as they performed numerous piano duo concerts as members of the 15th Coastal Artillery Corps Band, forging not only a life-long friendship for themselves, but also setting the stage for the storied association of the famed composer and the West Point Band.

After 18 months of Army service, Grainger, now a naturalized American citizen, flitted around the country, living and performing in a variety of locales from L.A. to Missouri, before settling with his wife in White Plains, New York. By the time he had settled there, Grainger’s dear friend and former colleague Resta had taken command of the West Point Band, a post he would hold until 1957.

With West Point just a brief train ride (or a slightly less brief walk, which Grainger was nevertheless known to frequently embark on) from his home in White Plains, Grainger soon became a regular visitor at the band, performing, conducting, and composing for the ensemble on numerous occasions, as well as using the band as his own personal “test audience” to try out new compositions and check his scores for errors before publishing.

With each visit to the band, Grainger’s esteem for the musicians at West Point grew. In recognition of the “glorious playing” of “the best-balanced, most artistic Band I know,” Grainger dedicated his Hill Song No. 2 to the ensemble, along with a short piccolo tune for the Field Music group aptly titled “Percy’s Tune.”

However, it wasn’t only Grainger’s musical skill that left a lasting impression at West Point — many band members from this time period can attest to the composer’s quirky escapades around the Academy.

Retired Sgt. Maj. Les French recounted one such colorful tale of Grainger’s brush with local law enforcement. Once while visiting the Academy, Grainger, an avid walker, took the opportunity for a scenic stroll along the Hudson River from West Point to nearby Cornwall-on-Hudson, accompanied by two band members. Their quaint journey soon turned into an utter ordeal as the three men were approached by police mid-way to their destination and charged with vagrancy. Grainger, who never carried a wallet or ID, was unable to prove his identity and was briefly jailed at the station, eventually getting bailed out by none other than his faithful friend at West Point, Francis Resta.

Far from keeping his trouble-making outside the gates of West Point, Grainger also caused a stir before a band concert in 1946 when he met Resta with a request for something that had never been discussed in their many years of friendship and musical collaboration: payment for his services.

Immediately ruffled by the request, Resta stewed over the conversation for a few hours before posing the obvious follow-up question, “how much?”

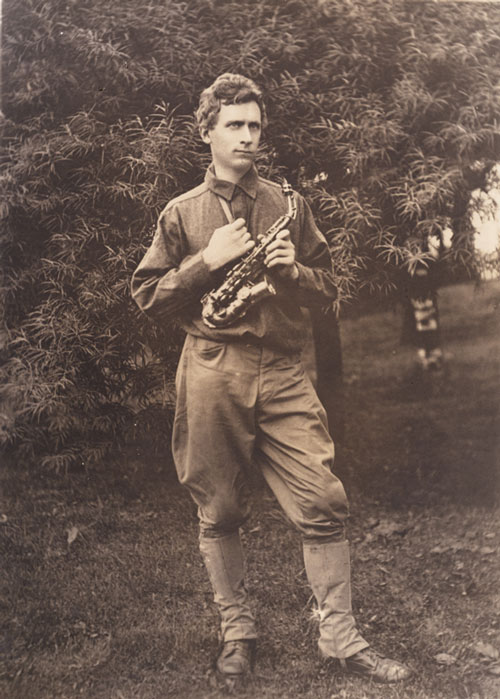

With a chuckle, Grainger named his price: one pair of official West Point parade trousers and a pair of combat boots, a request that Resta was more than happy to acquiesce, delivering them to Grainger in time for the evening’s performance — and for a photoshoot modeling the new attire in the band parking lot!

Grainger continued to perform regularly with the band until 1951, after which his health unfortunately began to decline. Until his death in 1961, Grainger spent most days at home building his own “free music machines,” the earliest experimental precursors to synthesizers. Unfettered by the constraints of traditional instruments in terms of pitch or beat, Grainger’s machines were inspired by everyday sounds such as trains, water splashing against a boat, the human voice, and even a squeaky door. His innovations in this area would prove significant in the evolution of electronic music.

Today, many remnants of Grainger’s life in New York can still be found at his home at 7 Cromwell Place in White Plains, which has for the most part been preserved as it was at the time of his death.